Your cart is empty now.

Sale

-20%

Sale

-20%

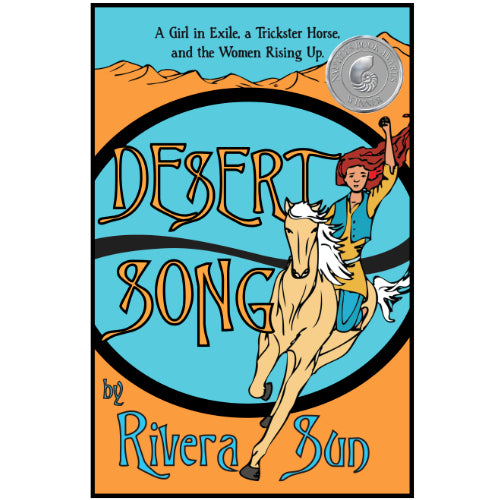

National Geographic says…“Kids are reading...the Ari Ara Series"

2020 NAUTILUS PRIZE - SILVER MEDAL!

A wild ride full of danger and adventure! Exiled to the desert, Ari Ara is thrust between the warriors trying to grab power…and the women rising up to stop them!

(Buy Direct - All books are signed and include stickers, bookmarks and a personal note.)

The world of her father's people is made of song and sky, heat and dust. Ari Ara wants nothing more than to be a proper daughter to her father, the Desert King. But nothing she does is right! She can't sing the songs correctly, her trickster horse bolts, her friend is left for dead, and Ari Ara has to run away to save him.

Every step she takes propels her deeper into trouble. A mysterious young songholder offers to guide her, a seer sends them on a wild goose chase, they rescue a young woman from a forced marriage - and accidentally set the army camp on fire! Before long, she's swept into a women's uprising against the warriors who are trying to seize power.

Ari Ara has to find her place - and her voice - in this strange culture…but time is running out. Warriors-rule rises across the desert. One by one, the women's voices are being silenced, cut from the Desert Song. Can Ari Ara and her friends restore the balance before violence breaks out?

This is Book Three of The Way Between – Ari Ara series. It is a complete story and may be read independently, but as one person said "The story of this book can stand alone but why cheat yourself?" They are fun to read in any order but best is to read the whole series!

Get them right now!...

Praise for Rivera Sun’s Ari Ara books

"...a beautiful experience...one that everyone in the world needs - now more than ever."

- Heart Phoenix, River Phoenix Center for Peacebuilding

"...this book couldn't have come at a better time. "

- Patrick Hiller, Executive Director, War Prevention Initiative

"...an impressive feat an exciting story that deftly teaches ways to create a world that works for all...outstanding contribution to the field of nonviolence!"

- Kit Miller, Executive Director, M.K. Gandhi Center for Nonviolence

"Five stars. It's Harry Potter with a contemporary message."

- Gayle Morrow, retired Y/A Librarian

" ...deserves an international audience."

- Amber French, Editorial Advisor, International Center on Nonviolent Conflict

"I highly recommend gathering the children around you and reading The Way Between and The Lost Heir so everyone can enjoy and embrace these masterfully-told, exciting adventures."

- Scotty Bruer, Founder, Peace Now

"Rivera Sun's creativity, wisdom, insight and joyful nonviolent activism for all ages fills me with awe and hope. If we were all to read her books the way we have read Harry Potter's, we would be well on our way to sending a different message to our children."

- Veronica Pelicaric, Author, Pace e Bene/Campaign Nonviolence

"...a beautiful experience...one that everyone in the world needs - now more than ever."

- Heart Phoenix, River Phoenix Center for Peacebuilding

"...this book couldn't have come at a better time. "

- Patrick Hiller, Executive Director, War Prevention Initiative

"...an impressive feat an exciting story that deftly teaches ways to create a world that works for all...outstanding contribution to the field of nonviolence!"

- Kit Miller, Executive Director, M.K. Gandhi Center for Nonviolence

"Five stars. It's Harry Potter with a contemporary message."

- Gayle Morrow, retired Y/A Librarian

" ...deserves an international audience."

- Amber French, Editorial Advisor, International Center on Nonviolent Conflict

"I highly recommend gathering the children around you and reading The Way Between and The Lost Heir so everyone can enjoy and embrace these masterfully-told, exciting adventures."

- Scotty Bruer, Founder, Peace Now

"Rivera Sun's creativity, wisdom, insight and joyful nonviolent activism for all ages fills me with awe and hope. If we were all to read her books the way we have read Harry Potter's, we would be well on our way to sending a different message to our children."

- Veronica Pelicaric, Author, Pace e Bene/Campaign Nonviolence

Throw-the-Bones – An Excerpt from Desert Song by Rivera Sun

This is an excerpt from Desert Song, a novel by Rivera Sun.

Up a long, winding ravine, tucked into a pocket meadow, lived a seer named Throw-the-Bones. Her home – if you could call it that – was a hide-covered lean-to half dug into the earth. A sod roof of desert grass grew above it; a rangy, horned goat bleated at them from on top. A desert chicken scratched in the dirt out front, scraggly-feathered with a flopping ochre comb. A dry bone-and-branch fence ringed the hut, white and stark, bleached by the blazing blue sky. Tala nudged Zyrh through the listing gate then slid off to push it shut.

“Leave it open,” a voice croaked out, dry as a spiny toad.

A hunched figure staggered toward them. Dangling locks of hair masked her face. Her grotesque cloak of rodent skulls, crows’ beaks, birds’ feet, and shed snakeskins lurched with every step.

“You’ll be leaving quicker than you came,” the woman rasped. “They all do.”

“Not Tala, Throw-the-Bones, you know that,” Tala called out soothingly.

“What’s that?” the figure cried with surprise, pushing back her matted hair and shading the sun from her eyes. “Tala? Well, that changes things. Come in for tea!”

Ari Ara blinked as the bedraggled figure dropped the rasping voice and tossed off a tangled wig. The slender, middle-aged woman cast aside the cloak with a look of disgust. She patted the stray wisps of brown hair back into place and straightened her spine. She wore a clean tunic and a bright blue belt. The wrinkles around her eyes creased at Ari Ara’s astonished expression and she burst out laughing merrily.

“The ole cloak-and-croak act is just to scare away unwanted visitors,” she said, “but a friend of Tala’s is a friend of mine.”

She winked and squeezed Tala around the shoulders. Ari Ara dismounted and followed the other two toward the hut. The woman turned with a brisk, no-nonsense attitude and eyed Ari Ara.

“You must know I’m Throw-the-Bones, but who are you? Potential Tala-Rasa?”

Ari Ara shook her head.

“Ari Ara Shirar en Marin.”

Throw-the-Bones’ mouth dropped open. Her eyes rolled back in her sockets. A tremor shuddered through her. Tala calmly pinched the woman’s nose, held her mouth shut, and counted to thirty. At thirty-three and a half, Throw-the-Bones threw Tala off, gasping.

“Thanks,” Throw-the-Bones coughed out. “Ack. That was a strong one. Good thing she didn’t come on her own.”

Tala let the wheezing seer lean on zirs shoulders and lurch into the shade of the hut. Throw-the-Bones settled in a chair as the young songholder gathered a trio of small cups along with a little clay teapot. The youth opened the lid and sniffed cautiously.

“Just a bit of spring mint,” Throw-the-Bones told the youth. “Nothing to worry about.”

She threw back her first cup and gestured impatiently for another while Ari Ara stood frozen in the doorway with an appalled look on her face, wondering what had just happened.

“Visions, love,” Throw-the-Bones explained, pointing to a three-legged stool and gesturing for the girl to sit. “Such a bother, really.”

“Wh-what would have happened if Tala hadn’t held your nose?” Ari Ara asked, tentatively sitting down.

Throw-the-Bones shrugged.

“Maybe I’d wake on my own a few hours later . . . or not.”

She shivered despite the red flush on her skin and sweat beads on her brow.

“Given the strength of these visions, I might never have come out of them, though old Stew’s trained to peck me back to life if I don’t feed him his grain on time.”

She pointed to the chicken, which stretched his neck and crowed before strutting out of sight. When Ari Ara turned back, Throw-the-Bones’ sharp eyes were fixed on her face.

“What did you see?” Ari Ara asked, clutching the edge of the stool and steeling herself. There was already one prophecy about her and it wasn’t pleasant. To her surprise, the middle-aged woman simply rolled her eyes and shoved her cup across the rough surface of her table for more mint tea.

“Oh no, it doesn’t work like that. Not even for you, though I’m sorely tempted to make an exception.” Throw-the-Bones leveled a stern look at Ari Ara. “No, no, if I risk death to see your future, you’ve got to pay prettily for that knowledge.”

“But I didn’t ask you to see my future!” Ari Ara objected.

“Precisely. Which is why I don’t charge for seeing, only for telling. I’ll be keeping my vision in my silence until you’re ready to pay.”

“You won’t tell anyone else?”

“Certainly not!” Throw-the-Bones retorted, looking insulted. “That’s unethical. Didn’t you explain?”

The last was directed accusatorily at Tala, who simply shrugged. The woman blew an exasperated sigh and turned back to Ari Ara.

“The bone fence, the skull cape, the raspy voice; that’s all for show. Idiots come to me to find their true loves or destinies. Most of them have lives so dull it pains me to wade through the visions.”

She rubbed her temples. People lived. They tended goats. They met a girl. They married a boy. Children were born.

“Everyone dies,” Throw-the-Bones sighed, “and I always see that. It’s where I get most of my knowledge, though no one likes to hear that. I peek in at the funerals, count the wedding rings and scars, notice how many children have gathered, and look for any telltale callouses on people’s hands. That’s enough to hint at a life . . . though occasionally, I see more. Wars and famines. Bold lives and cowardly deaths. Simple existences and perfect happiness. Long-living elders and easy exits. Short flickers and sudden snuffing outs.”

Throw-the-Bones’ face grew shadowed. Her fingers clutched the clay cup hard enough to turn her knuckles white.

“I can see why you wouldn’t want too much company,” Ari Ara said gently. “I’m sorry if hearing my name caused you distress.”

The brown-haired woman looked up. Her eyebrows lifted.

“In all my years,” she murmured, “no one has ever said that.”

She held out her hand and squeezed Ari Ara’s palm in gratitude.

“When the day comes that you face a crossroad of no clear choices, come to me, and I will tell you which way you went.”

“You could tell her now,” Tala pointed out, “and spare her the trip.”

Throw-the-Bones snatched the teapot away and sloshed some more in her cup.

“You are both too young to know the wisdom of anything,” she grumbled. “Especially you, cheeky Tala. Such impertinence! Do I tell you how to sing the old songs? No. You do your job and trust me to do mine.”

Tala looked sufficiently chastened . . . at least until the youth tossed Ari Ara a hidden wink behind the seer’s back.

“But none of this is the question you came to ask, is it?” Throw-the-Bones asked suddenly with a sharp astuteness, looking from one to the other.

“I need to find my friend Emir Miresh,” Ari Ara explained.

“The Marianan warrior?” Throw-the-Bones asked in surprise.

Ari Ara nodded and related the tale of how she lost him.

The woman listened with a troubled expression. She tapped her fingers on the wooden table in agitation. She grimaced.

“Oh, I hate this,” she groaned to Tala. “Take the cups and fetch the bones.”

Tala cleaned everything off the battered table. Ari Ara stared at the surface . . . the blackened gouges looked like a map . . . ah! She tilted her head; it was the desert. There were the mountains, the foothills, the winding streams and rivers. Thin red lines wove in intricate patterns through it all, perplexing her. She reached out to touch the web. Throw-the-Bones slapped her hand away.

“Don’t meddle. I’m going to find your friend’s bones, living or dead.”

Ari Ara blanched.

Tala returned with a basket of old bones, large and small, some shiningly clean, others with bits of gristle still attached. Throw-the-Bones began to ask her a series of questions about Emir.

“Short or tall?”

“Tall.”

She picked out the tiny fish and bird bones and discarded them to the side.

“Old or young?”

“Young,” Ari Ara answered, watching the woman’s hands fly as she tossed out the cracked and yellowed old bones.

“Color of eyes?”

“Uh, blue, I think,” Ari Ara stammered. She hadn’t really thought about it.

“Hmm, not clear enough,” the seer answered. “Stout or slender?”

“Slender.”

“Water or fire?”

“Water. He’s like a river when he moves.”

Each time she answered, Throw-the-Bones sorted out more bones until the choice was down to two. She weighed them in her palms, thinking, then set aside one.

“Here, hold this,” the older woman ordered, tossing the other vertebra to Ari Ara.

“Ew!” she screeched, dropping it with a disgusted grimace. There were still red tendons attached to it.

Throw-the-Bones eyed her, shook her head, and picked the bone up.

“Hmm, how about this, then?” the woman asked, turning suddenly and snatching something off the high shelf behind her.

It was a strange stone, smooth with time and a river’s touch, black as ink, and warm against Ari Ara’s palm.

“What is it?” Ari Ara asked, holding it up to the light.

“An old thing from long ago,” Throw-the-Bones answered. “A tree’s heart turned to stone by lightning. A bone that is not a bone.”

She stretched out her hand. Ari Ara gave it back. Throw-the-Bones nodded approvingly as she rolled back her sleeves and weighed the lightning stone in her palm.

“Your friend has a very old soul and a truly good heart. If we find him, don’t lose him again,” the seer advised her. “You do not find friends like him every day.”

Ari Ara nodded silently, suddenly hot with embarrassment over the way she’d treated Emir. Throw-the-Bones began to chant in a low voice, cupping her hands around the lightning stone. She shook her hands, slowly at first, then rhythmically, chanting faster and faster until she opened her palms above the table. Her eyes traced the arc of the fall to where the stone landed squarely with a single thump, no bounce, no spin.

“This is Moragh’s Stronghold,” Throw-the-Bones stated, pointing to a black mark slightly east of the stone. “You last saw Emir here, just to the northwest.”

Ari Ara nodded. Throw-the-Bones picked up the lightning stone. She repeated the chanting and shaking, though the words changed slightly. A crackle of energy snapped through the hut. Her hands split open. The stone fell. It hit the mark northwest of the Stronghold then spun and spun and spun along the red lines, wavering from one side of the table to the other, traveling the length from north to south. Finally, it came to rest in the Middle Pass of the Border Mountains.

Throw-the-Bones scowled and harrumphed in surprise. Ari Ara opened her mouth to ask, but the woman lifted her hand for silence.

“Tala, sing the Truth-Telling Song.”

“But – “

“Do it!”

All the hairs on Ari Ara’s arms rose up as the two voices joined, one singing, one chanting. The air tightened as if bound by an invisible noose. Throw-the-Bones shook the stone between her palms. Her whole body rattled with the gesture, quicker and quicker. Then, the woman’s hands flew open. The lightning stone hit the table and spun in place for a long moment. It fell at the exact same spot as before in the middle of the Border Mountains.

Tala squinted at the table. Throw-the-Bones scowled and folded her arms over her chest.

“That,” she stated flatly, “was not what I was expecting.”

Ari Ara couldn’t stay silent any longer.

“What? What does it mean?” she blurted out.

Throw-the-Bones’ fingers stretched out.

“There is where you left him.” She pointed to the first spot then moved, tracing the wandering pathway of the second toss. “This is where he has been . . . or will be,” she said. “It’s never exactly clear.”

“So, he’s alive!” Ari Ara cried in relief.

“Maybe,” the woman answered with a scowl. “Maybe not. A spinning bone indicates that someone is on the edge of life and death, spirit and mortal life. I have never seen a bone dance the threshold line as long as that. It is strange.”

Throw-the-Bones tapped her chin.

“The third toss is where you will meet again. Here in the Border Mountains. But your friend still spun the spirit-mortal dance. Why would anyone move him over all that distance if he were sick or injured or near death? That, I cannot understand.”

She had thought the bones hid the truth on the second toss; that’s why she had Tala sing the Truth-Telling Song. The melody made the bones fall honestly.

“Whatever that was, it’s speaking the truth.”

“When should I meet him there?” Ari Ara asked, pointing to the mountains.

Throw-the-Bones looked up, eyes clouded and distant.

“Do not seek him. Your paths will find each other.”

Then she shivered out of her reverie, stoked the fire, and refilled the teapot. She bustled about the hut, ignoring Ari Ara’s pestering questions, packing away the bones, replacing the odds-and-ends on the table, tossing a handful of grain to Stew the Chicken. Tala quietly rose and gestured to Ari Ara to follow; they’d get no more out of Throw-the-Bones.

“Wait.”

The woman’s voice stopped them as they left. She snatched the lightning stone off the table.

“Take this.”

“I couldn’t,” Ari Ara protested.

Throw-the-Bones shook her head.

“It is tied to him now. I can’t use it again.”

She grabbed Ari Ara’s wrist, turned her hand over, and placed the black stone in the girl’s palm.

“There is the matter of payment, too,” Throw-the-Bones said sternly.

“I have little – ” Ari Ara began.

The woman held a finger up to her lips and tilted her head as if listening . . . or remembering.

“You will travel the dragon ranges, the desert ridges, the marshlands, the desert sands,” she chanted in an odd, distant tone. “Your paths will crisscross past the Crossroads, but your eyes will not meet until after the women and warriors collide, and the exile is exiled from exile.”

Throw-the-Bones’ eyes rolled back in her head. She shivered. The woman’s limbs shook from head to toe. She gasped as if she was resurfacing from a deep dive into a cold lake. She braced her trembling palms on the table.

“For payment,” she croaked, “you will promise me something.”

“What?” Ari Ara asked warily.

“When the young warrior returns, the old warrior will ask for your help. You will give it,” Throw-the-Bones stated firmly.

A shiver and tingle ran through Ari Ara’s spine. She nodded.

“No more questions now,” the seer insisted. “I have no more answers for you.” She hustled them out the door, onto Zyrh, and beyond her gate. As the latch clicked into place, she eyed the redheaded girl riding away. She had no more answers for Ari Ara Shirar en Marin, not until they next met on the long road called life.

This was an excerpt from Desert Song, a novel by Rivera Sun.

At its heart, Desert Song is a story about finding your voice. It's a story about finding the courage to speak when others try to silence you.

Desert Song is about a culture at a tipping point. How do we assert, at the very moment that counts, that everyone has a right to exist and shape our society on equal footing?

What are the moments where we sense that we are standing at a precipice or at a crossroads? How do we step back from a dangerous path?

Questions of how to ensure equality, justice, peace, and democracy are some of the most important questions humanity has yet to answer. That's why I explored them in Desert Song.

Women warriors and teen girl assassins are in vogue right now. But we have to ask: is it really an achievement for women to succeed in the structures and systems built by patriarchy, domination, racism, classism, and exploitation?

I am always interested in the stories a culture tells - myths, fables, urban legends, movies, bestselling novels, folk tales - and the reasons we tell them.

If we're not careful, finding our empowerment through violence or the military will turn us into the oppressors of others.

Can a warrior be someone who is nonviolent? Mohandas K. Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. thought so. Badshah Khan, a friend of Gandhi's who built an 80,000-person nonviolent peace army thought so.

It is my belief that the violent warrior archetype did not define courage and ferocity for humanity, he/she/they borrowed those qualities from other sources.

It's time to reclaim courage and ferocity from war and violence. Nonviolent heroes and sheroes have shown incredibly fierce courage in countless struggles.

Desert Song is a novel that takes risks. It explores complex ideas.

It doesn't fit into neat little boxes or black-and-white frameworks. It doesn't offer easy answers. Instead, it makes us ask important questions.

Desert Song helps us see our world in new ways. It helps us think about our lives differently. To me, this is exactly what a good novel should do.

Desert Song is story about people who don't fit into the world they were given . . . so they set out to change the whole world, together.

"In the desert, we believe that everyone is part of the Harraken Song - the collective music of all our voices, the song of all of our lives - and thus, everyone's voice must be heard in the village sings."

When voices are silenced from the Harraken Song, Mahteni thought darkly, the music is not complete. The decisions weakened and faltered. The harmony became unclear. Discord was sown between people. Resentments built into hatred.

The desert was a land of harsh beauty and wild skies, evocative songs and proud people. It was a land of magic and legend . . . and a place of many dangers.

In the ruins, the old warrior told stories of peace to the youths, wishing he had listened more closely all those years ago.

If his ancestors' fear, long ago, had not driven them to train their children in violence and warfare, that madwoman would not be seeking vengeance from him today.

"There have been many times when I faced a choice between killing or being killed," the old warrior confessed, "but long before those moments, my path was littered with choices - not easier ones, but choices that could have kept me out of that final deadly decision."

Desert Song is a story about reckonings. The violence of the past catches up to the characters. Old blood feuds haunt them. Fortunately, this is also a story about how we break those cycles.

Song was the link from the past to the future. It was how the living threaded the wisdom of the ancestors into the world they would leave to their descendants.

The Way Between could be used physically to interrupt fights and stop violence, but that was just the beginning. There were inner and outer practices. There were individual and collective ways to take action.

The Way Between organized people to neither fight nor flee from the conflict. It offered dozens of ways to remove support from a problem and build a solution, instead.

A war can't happen if no one shows up. If the soldiers don't go, or the nobles won't pay for the soldiers to go, or the smiths won't make weapons.